Karen Rose and I promised not to give advice, so don’t think of this as advice, rather encouragement.

First of all, why not retire? There’s nothing that says you shouldn’t. It’s completely your own decision. Retirement right now could make you part of the Great Resignation—and who doesn’t want to be a trend-setter? So, in the spirit of all the self-help gurus who have gone before me, here’s my list of how-to’s.

- Tell your friends, family, and colleagues how you want to celebrate. You could have a bonfire or even a Zoom meeting (I’m kidding). Restaurants and bars are starting to open. It’s not impossible anymore. I like cake, so that’d be my go-to, a Danish layer cake from a bakery in Racine, my hometown, or if not available, a big white cake with white frosting from Whole Foods with vanilla flavor—you might be trying a lot of new foods when you retire, that’s one way to pass time—eat.

If you retire in summer, you can always have an outdoor party. In fact I went to a couple last summer, and the retirees didn’t seem intimidated by the pandemic at all. And there was lots to eat—even cake.

There’s always the person that wants to go quietly. The one who rather slides into retirement; some even take it year by year, never really announcing it until they’ve completely left the playing field (E.g., KRS?) It’s not a bad way during a pandemic, or during any hard times, as everyone is busy watching CNN, the CDC, NBC, OSHA, SCOTUS, ETC.

- Let those feelings come forward. Maybe you’ll be relieved—you’ve had enough of working for a lifetime. You might be discombobulated—I certainly was. That first Monday morning after my drinks at the bar party—no, I didn’t get cake—left me unmoored. Should I wear jeans? Jeans are for weekends. What time should I have breakfast? Lunch? What am I going to work on? Does my spouse have to be near me all the time? I can hear him rattling around the house. Is he always like this? When do I get to “quit” for the day—oh, I never started.

You will have feelings. I promise! Let them all hang out!

- If you live with someone, warn them. They may have had the house all to themselves, but that’s changing. Someone new will be sitting on the couch reading the morning paper, playing the stereo during the day, making lunch right when they like to make lunch. Maybe you’ll start to clean closets, throwing things out. Someone else might not be ready for this. And are you ready? Your close relationships will change, hopefully for the better.

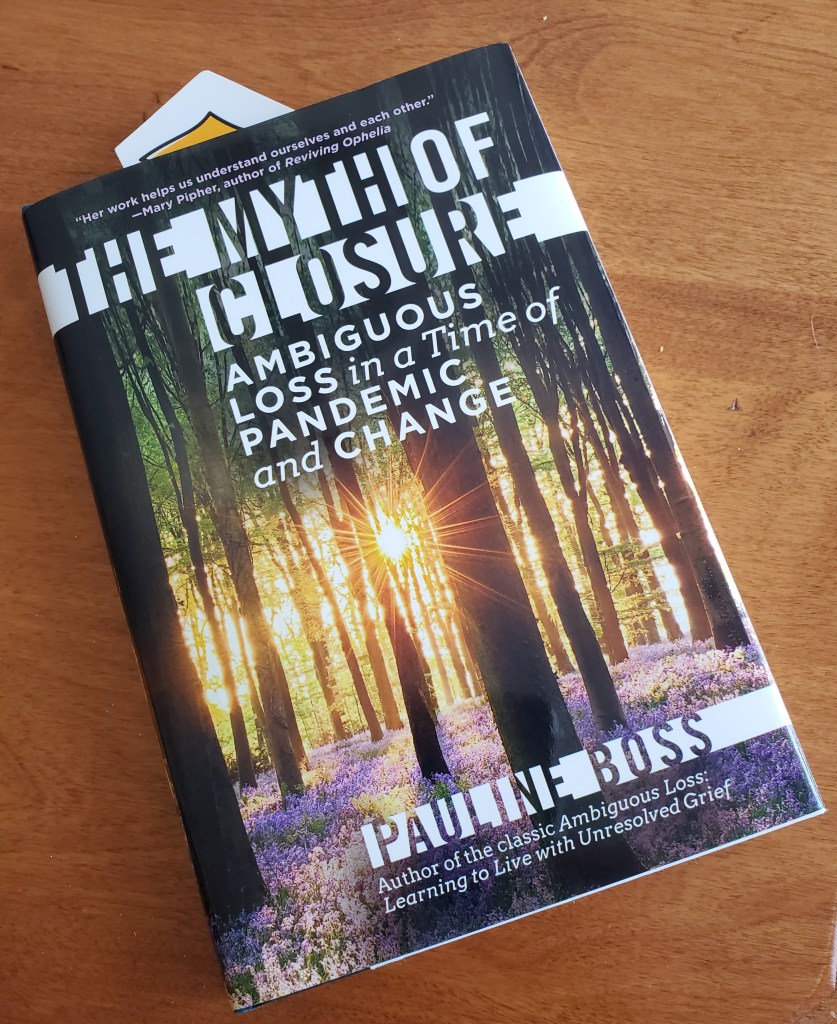

- Don’t sweat having a purpose. This is a biggie! I know, you’ve read all those books about the importance of having a purpose when you retire, Something to Live For, Retirement Reinvention, Purposeful Retirement, and Encore Adulthood—among the many—but I’m here to tell you retirement is all about the unknown, and that’s what makes it both interesting and challenging. In the world of work, you needed goals. The idea was to get ahead, to strive (more about this from Karen Rose), to seek, to find. . . to make a name for yourself, do better than meeting quotas, etc. You are done with all that. New paradigm coming your way! And you get to create it.

The Purpose experts argue that having a purpose is linked with better outcomes for aging, living longer, etc. But you’re not an outcome, a statistic. You are you, and if you don’t have a purpose, that’s just fine. I’ve written about Big P and Little p, arguing that Big Purpose is a male oriented way to live and that there are lots of Little purposes in our daily lives—relationships, family, great books, helping out in the community, that can evolve daily. By letting go of the need to find some big, all encompassing Purpose, you can let the day’s own offerings be sufficient—and you’ll be more inclined to show up for them, because you won’t be busy searching for that big Purpose.

If you have a big Purpose for your retirement, by all means, go for it. My take is because so many of us love our lives but probably can’t identify some big Purpose in how we live them. But then living a moral and kind life is rather a big Purpose.

Instead of worrying about purpose, resolve to be CURIOUS–like the Torstein Hagen advertising for Viking Cruise Ships. When the pandemic first hit, and we were all scared, staying home, isolating, I started daily walks—like everyone else—around the little lake by our house. After several of these walks, I noticed stumps, which had been cut off in the prime of life, had branches growing out of them; they were putting out shoots of hopefulness. I photographed these stumps and shoots and followed them throughout the spring. I saw them turn green and produce leaves. Later a friend told me about something called coppicing, a process used to manage forests by taking advantage of these persistent trees. What astonished me about this discovery was how I’d walked by it most of my life! (https://karensdescant.com/2020/04/20/condition-provisional/0)

So be easy on yourself about purpose. Maybe you’ll find one, maybe you won’t, but retirement allows you time to be with the unknown, to pay attention to the details, or, as a friend once advised me—to smell the roses.

- Let go of expectations! I absolutely believe that we would all live happier lives if we could let go of expectations. In the dictionary, 1) expectation is defined as the state of looking forward to or waiting for something. 2) A belief that someone will or should achieve something. Until the pandemic, retirements were full of expectations—“I’m going to travel.” “I plan on spending more time volunteering.” “Maybe I’ll take some classes.” All worthwhile endeavors, but this pandemic has certainly put us on pause.

So what recourse do we have? We could approach our new retirement lives without those expectations, instead curious and willing to engage with what shows up. You now have time to explore who you are inside and act from within rather than without, based on expectations set by others, the society, and eventually by ourselves.

If you’re planning on retiring, go ahead. You will have a chance to approach life with curiosity, seeing what unfolds, and maybe, with that curiosity, learn more about yourself and the world around you. I wouldn’t normally turn to the Rolling Stones to talk about retirement, but their song, No Expectations perfectly sums up my idea for approaching retirement:

Take me to the station

And put me on a train

I’ve got no expectations

To pass through here again.

A retired Keith Richards