A few weeks ago, I went with a small group on a pilgrimage to visit Selma, Montgomery and Birmingham. According to Wikipedia, “A pilgrimage is a journey to a holy place, which can lead to a personal transformation, after which the pilgrim returns to their daily life”. We are called to a pilgrimage, whether it is to Mecca, Santiago de Compostela, or a 10-day silent retreat in the wilderness, because it is connected to our spiritual beliefs and commitments. A pilgrimage is not expected to be fun because transformation is challenging, even when the pilgrim experiences joy – and this was my first.

It is a stretch to think of Alabama as a holy place, but I was called to learn from sites where social and personal transformation occurred during one of the darkest times in American history. I expected that the weight of what I would see would be too difficult to bear alone, and I knew that I would depend on the group. I anticipated visceral and emotional experiences while immersed in places and events that I experienced, as a white, northern adolescent of the 1960s, only on a small black-and-white TV.

–National Memorial for Peace and Justice

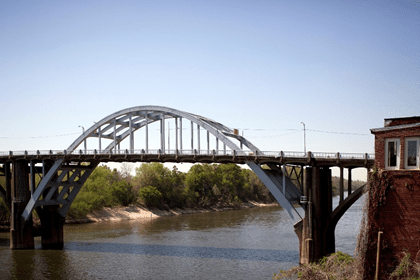

Some of these challenges were obvious, as we silently crossed the heavily traveled Edmund Pettus Bridge, caught in the horror of Bloody Sunday. Or while I mourned, in overwhelmed silence, in the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, built as a sacred space to honor over 4000 people who were documented Black victims of lynching between 1877 and 1955. Each experience was painful, and each day exhausting, but they left me with a desire to go on, to understand more.

But there were cracks in the darkness, reminding me that a pilgrimage is about being open to something new….So, unexpectedly, I found hope, even while contemplating the vast evidence of the “whitewashing” of my country’s history that began shortly after the end of slavery and continues, only minimally disrupted, in the national collective conscience. I found hope –in the stories of people who participated in the boycotts and the marches, whose message was less words than the continuing display of commitment, persistence, and the capacity to overcome fear for a wider goal. And I also came across younger people who are working in new ways.

I found hope at The Mothers of Gynecology Monument, a small, privately conceived and owned enterprise, whose development was the vision of Michelle Browder. I use the term enterprise carefully, because the small lot in an inauspicious area of Montgomery did not announce its radical message on the outside. Only when we parked our van and entered did I realize that Michelle, the artist who conceived it, did far more than create monumental sculptures memorializing three slave women whose bodies were subjected to a variety of experiments by Dr. J. Marion Sims, who became famous as the Father of Modern Gynecology.

The sculptures are magnificent, evoking both the dignity and the pain that Anarcha, Betsy and Lucy endured. And they are technically beautiful, taking welding (not a common art form for women) and use of materials to a level than I have not previously experienced. Unlike a Calder mobile, with its distinctive simplicity of form and movement, Anarcha, Betsy and Lucy are vividly ornate, surprisingly fleshy given their metallic glow, and terrifying in their portrayal of the consequences of involuntary, unanesthetized surgery. They are also queenly and stoic, survivors in the face of slavery and savagery. If anything, I thought of them as contemporary versions of the Greek kourai – the monumental females whose bodies hold up the Acropolis.

Michelle uses art as a starting point for social action – Artist as Change Agent. Also within the Monument is a modern van, outfitted as a traveling gynecological clinic that she and her staff take out to women who do not have access to quality care. After purchasing Dr. J Marion Sims former downtown Montgomery office, she removed a plaque lauding his accomplishments — and installed it as part of an sly artistic reimagining of what the experiments might have been like if their subject was a middle-aged White man. His office is being re-purposed as a women’s health clinic. Not content to limit herself to Montgomery, Michelle and her collaborators are developing educational centers and annual conferences to examine racial disparities in women’s health. If Michelle – artist, activist, and social entrepreneur – is not cause for hope, I can’t imagine where I will find it.

My pilgrimage added to my old story — that the civil rights movement’s non-violent challenge to oppression nudged the needle of justice toward freedom but left oppressive structures largely untroubled. But it also revealed new stories of subversive and novel ways of upending the story that nothing has changed or is changing. Knowing the story. Looking for more within the story. Re-telling the story in new ways. Taking the story inside and into the world to speak to our hearts. That is what spiritual development is about. My transformations from the pilgrimage continue to emerge. What I did not expect was hope, yet that is what stands out.