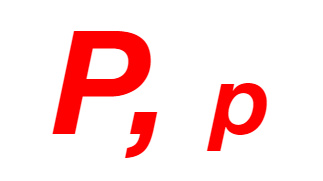

The ubiquity of retirement “experts” telling seniors they need a purpose borders on tiresome. Hammering about purpose as necessary for giving meaning to life seems quite male to me, a sort of Big P (and I don’t have to tell you what else begins with p). It’s as though the adjustment to retirement converges on this one construct—Purpose—as a solution. But what if my way of adjusting to retirement is constructed from my web of relationships, interests, opportunities, family, etc? What if it’s not only ONE big purpose that drives me and helps the world, but a series of small day-to-day purposes, little p’s. To me that would be a more female way to consider the idea of purpose.

Trying to scrub the Big P notion out of my mind and come to what gives me meaning led me to recall three women whose careers I’ve followed closely, probably because they are writers, but also because their lives took such different paths where purpose is concerned: Rachel Carson, Carolyn Heilbrun, and May Sarton. I’ve listed them in the order that they entered my life, because recalling them in that order has helped me form my idea of Big P, little p.

I was an undergraduate at the University of Minnesota when I read Rachel Carson’s book, Silent Spring. I remember reading it during those big lectures of 300 or more students in biology, underlining it frantically; reading it whenever I had a break in my day; carrying it everywhere with me.

Carson, a woman with a Big P, believed that the rampant escalation of chemical use in our environment was harming the biosphere—she called these chemicals biocides. Carson wrote much of Silent Spring while undergoing chemotherapy and radiation for breast cancer. She kept her illness quiet because she thought if the chemical industry knew, they would claim she had a personal vendetta in writing the book. In fact, her entire career of nature writing culminated in this book. Sadly, Carson died of her cancer two years after the book was published.

As an idealistic freshman, Carson inspired me to want to do something big that would make the world better; I think we all hold similar aspirations at that point in our lives. My direction turned out to be marriage, family, and teaching school, most of which kept me busy enough that I didn’t pause often to reflect on whether I was changing the world. I kept putting one foot forward—after all, aren’t raising happy, well-adjusted children and educating the young gifts to the world?

Many life events and years later, I encountered the Kate Fansler mysteries, written by Amanda Cross, a pseudonym for Carolyn Heilbrun, a professor at Columbia, and the first woman tenured in the English department.

At the time, I was working on my Ph.D. so reading mysteries by a professor had special appeal. Later, during my MFA studies, I ran into Heilbrun again, this time in her book, Writing a Woman’s Life. Then, as I reached my late 60’s I encountered her a third time in The Last Gift of Time: Life Beyond Sixty. This was the book that held my attention. The prologue is essentially an argument for life being over at 70. She notes, “is it not better to leave at the height of well-being rather than contemplate the inevitable decline and the burden one becomes upon others?” She also states, “I was—and am—one of those for whom work is the essence of life.” And that I think is where she sold short the possibilities life affords. Heilbrun committed suicide at age 77 by taking a sedative and putting a plastic bag over her head. She left a note that read, “The journey is over. Love to all.”

I read about Heilbrun’s suicide mid stroke on my exercycle—She really did it. She meant what she said. It took me days to process her suicide. I even wrote about it in my application to the MFA program at the University of Minnesota. Heilbrun had much to live for, a loving husband and family, grandchildren, good health, a successful career, respect, etc. It made no sense to me to define one’s life solely in terms of work, which I presume she did. Once she anticipated a decline in the Big P of work, she wasn’t willing to construct a life that included both some, though less, Big P and also more of the many little p’s of everyday living. She was and still is for me a cautionary tale about nurturing both curiosity and flexibility.

Which brings me to my last admired female writer, May Sarton. I know Sarton primarily through her journals, which many critics believe to be the best of her 53 books, most of which are novels and books of poetry.

Starting with I Knew a Phoenix, published in 1959 until her last journal, At Eighty-Two, published in 1997, two years after her death, Sarton chronicled aging, isolation, solitude, friendship, building and loving a home, relationships and more. What stands out for me is that although Sarton started out with the Big P of an ambitious writer, she matured into a person who accepted, albeit with regret, that her work was not considered part of the literary canon of her time, and she went on to cultivate the many little p’s of her life. Her journals charm with details of daily life: ordering bulbs for the garden; walks with her beloved dog, Tamas; visits and long talks with lifelong friends; keeping a lively correspondence, sometimes with complete strangers; and following the antics of her various cats and neighborhood critters around her secluded house in Nelson and later on the coast of Maine. These were the small p’s of the solitude she captured in her journals into old age. I keep a Sarton journal next to my bed and read some every night before turning out the light.

I’m not writing to criticize anyone who has a Big P in their life. No way, it’s a gift. I myself will always sustain a passion for teaching and writing, the stuff of Big P. But I am arguing that a web of little p’s has the substance of a Big P and of a life well-lived. A few days ago, I woke up excited to attend my grandson’s senior speech—before the Corona Virus put a lock on outside life. I had an exciting small p purpose for my day. Now, as I recall the day with my family, the speech, the cheers, the hugs, the brunch after, I realize that while the search for a new Big P to enliven retirement has been, for me, akin to finding a four-leafed clover in my lawn of Creeping Charly, most days I have little p’s everywhere. I walk my dog around a lake that changes with the seasons; I have lively lunches with friends; I enjoy dinners and vacations with family. My latent Big P for writing and teaching will always be part of me, and meanwhile, every day has something to savor, right until the moment when my cat walks across my face before settling at my feet for the night.