When is a 1992 Ford Tempo the grandest car on the road? When you are 48, and it’s the first car you’ve ever owned. Mine was black, and I was convinced it passed for a BMW with its plain grill, sleek lines, faux black leather interior, and silver trim. Every Saturday I’d drive it through the gas station car wash, then dry and shine every inch of it. I also didn’t drive it much because I was in graduate school and my bicycle was easier for getting around the U of Minnesota campus.

Growing up in Racine, Wisconsin during the 50’s, I never got a ride anywhere. If I asked my stepfather to take me someplace, he’d say, “No,” followed by, “If you want to go bad enough, you’ll figure it out.”

I did. I took the bus, rode my bike, or walked. Once a week, I’d travel by bus uptown for my music lesson at Gosieski’s Music Store. I had to transfer, and to deal with the boredom of waiting for that second bus, I memorized all the car makes, models, and years, so when I grew up and could buy a car, I’d know which one I wanted—a Chevy Bel Air or a Packard Patrician or maybe a Ford Fairlane? Someday I’d have a car of my own, and I’d drive everywhere—no more waiting at bus stops, bicycling, or walking home late at night, scared. And I’d give people rides, too! I would not be stingy with my beautiful car.

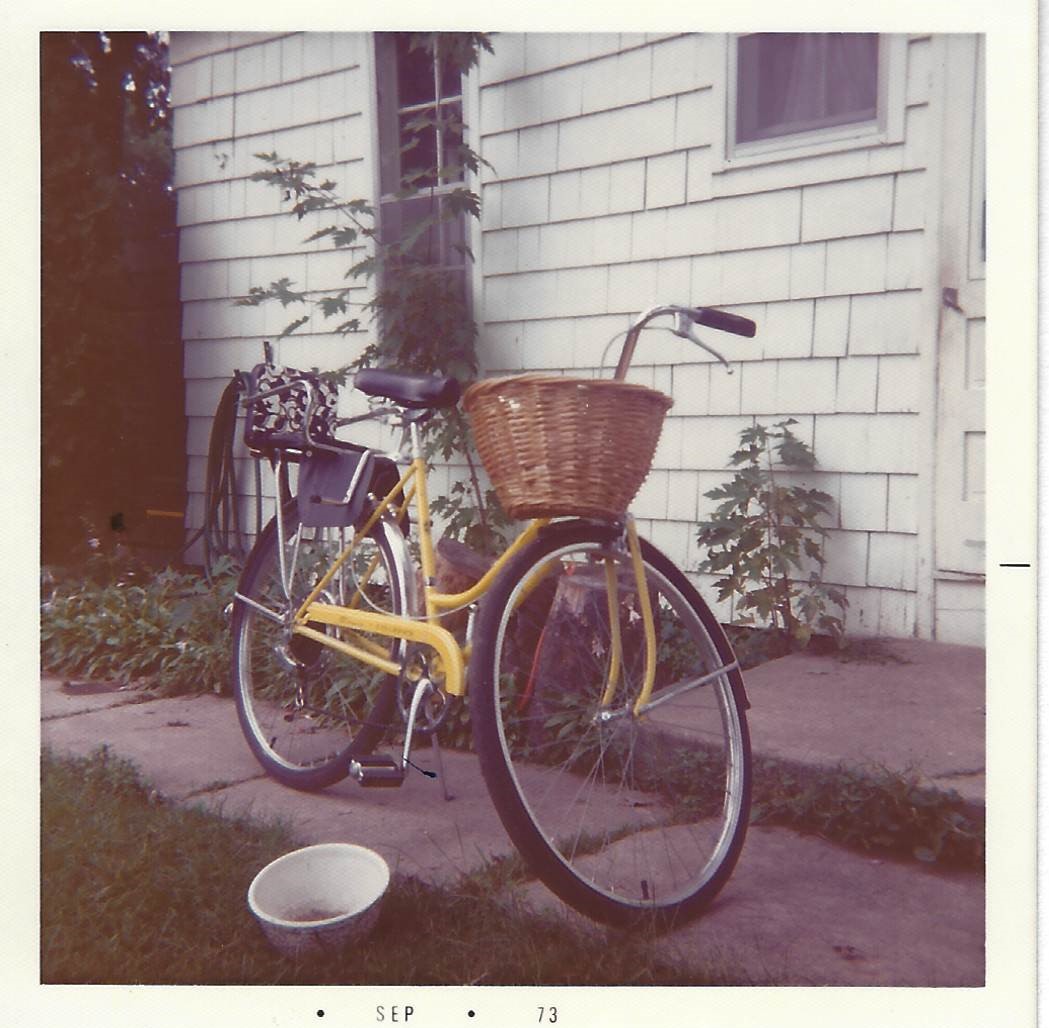

As it turned out, I waited a long time to achieve my dream. In my undergraduate years, my main transportation was a Dunelt three speed (that precursor to Raleigh bikes now lists on eBay for $2600). Then marriage. Though I finally learned to drive, I was usually at home with two young children because my husband needed our only car for work. But I wasn’t easily deterred. I quickly initiated my children into cycling, walking, or taking the bus. I remember standing on the side of the highway in Minnetonka Beach (exurban Minneapolis), next to the lake and across from St. Martin’s church with two young children to take the bus into Wayzata (a closer-in suburb) or the city. I never let a lack of transportation stop me from doing what I wanted to do.

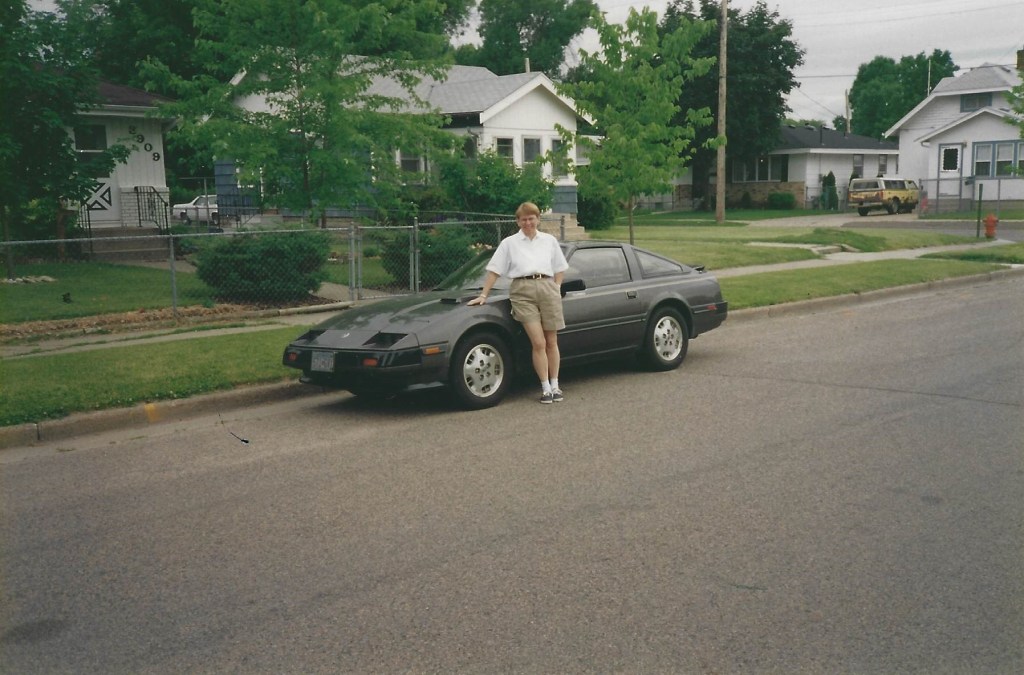

We divorced in 1991, and in January 1992 I bought my first car, that snappy Ford Tempo. It spoke freedom to me, not having to wait interminably for a bus, not being dependent on someone else’s availability for a ride, or riding my bicycle after a long day. I could go where I wanted when I wanted. The American dream, finally accomplished.

My years of waiting and wishing and that Ford Tempo planted the seeds of a love for cars. Shortly after I bought the Tempo, I met my second husband, who convinced me to trade it in for a Mazda RX7—something sportier. I was off on my journey of newer, better cars—as often as I wanted. Now it’s the latest technology and design that catch my fancy—don’t you love the new powdery colors on the 2024 models—like “Cosmic Blue Pearl?”

So here I am at seventy-nine. When my husband suggests making do with one car or using the bus more, I am adamant: I spent nearly forty years riding the bus, walking, bicycling, or sharing a car. I want my car and the freedom it gives me.

But that fierce position is threatened—I am aging. Although I feel sharp with good reaction times, I know I’m not the person I was in my 40’s—the age group with the lowest accident rate. Weaving in and out on a freeway often feels treacherous to me—more so since I was rear-ended by a semi a few years ago. So I stay in the right or middle lane and accept that I’ve slowed down.

When I looked up the average age that older people stop driving, I was astonished when one website claims that it’s 75! (The National Institute on Ageing states that is not possible to calculate this number). I read on to find out all the reasons people stop driving—arthritis, making it difficult to grip the wheel, eyesight issues, diseases and medications. I suddenly felt extremely lucky not to have these issues.

For all the hype about dangerous older drivers, The National Institute on Aging states that “Therefore, we must be careful not to judge the safety of one’s driving solely based on their age;” it’s the millennial drivers who have the most accidents. The 75+ group has the fewest, although they are more likely to die from an accident because of other underlying conditions (remember Covid?).

So when should I stop my ongoing love affair with cars? I haven’t experienced the behavioral indicators, like stopping when there’s no stop sign, not following traffic signals, side swiping, etc., but it’s helpful to know these. Yet, contemplating not driving is almost as scary as being told I’ll have to stay home and watch TV the rest of my life—which is the nightmare I conjure up when I imagine what would happen if I stop driving.

All this aside, I don’t think society does much to help older drivers. Right now the push in Minneapolis is to get us all on bicycles – like the Dutch, who give up their bicycles only when they are consigned to a nursing home. I ride my bike recreationally, and I’ve started doing short errands on it. I want to be part of the solution, but I’m not sure that bicycling to the grocery store when I am 90 is realistic. As one of my friends put it, “It’s not if you fall, it’s when.” For now I’m happy that I’m driving and can still ride a bicycle— and walking, well, my knees don’t love it, but I subscribe to my stepfather’s words, “If I want to get there bad enough, I’ll figure out a way.”