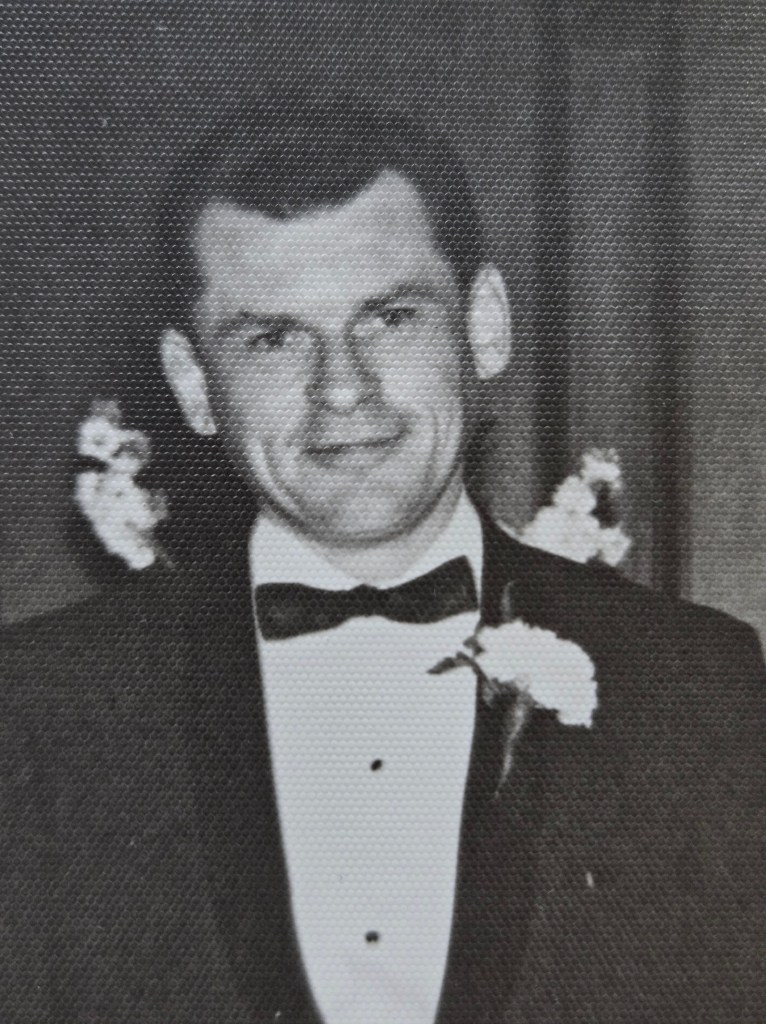

My stepfather, Don, loved three things in this life: my mother, fishing, and tinkering, especially under a car. Don adopted my two sisters and me when I was ten. He was boyish, enthusiastic, deeply in love with our mother, home from WWII (He’d joined the army at 17.), and excited to start his life. He always had a project going. Take the worm farm he built outside our front door. What ten-year-old isn’t fascinated with a worm farm? It was my job to carry out the scraps from dinner and to turn over the dirt. When it came time to go fishing, I got to fill a can with squirmy night crawlers.

Don always planted a vegetable garden. He’d give me a packet of radish seeds to sow because radishes come up fast. I witnessed the marvel of seeds. He put me in charge of weeding. After pulling weeds a few times in the hot sun, I suspected he had tricked me into doing the hard part of gardening. But I didn’t mind. I felt important.

He built new stairs for our house. I watched him saw pieces of plywood in a stair shape and then lay planks across the cuts. He leaned them against the garage where we could climb up and down. Next he added a picket fence to our yard, drilling the post holes, another curiosity for me to see. It seemed as if he could do anything.

Don bought a Webcor turntable, and Bozo the clown records that I listened to over and over.

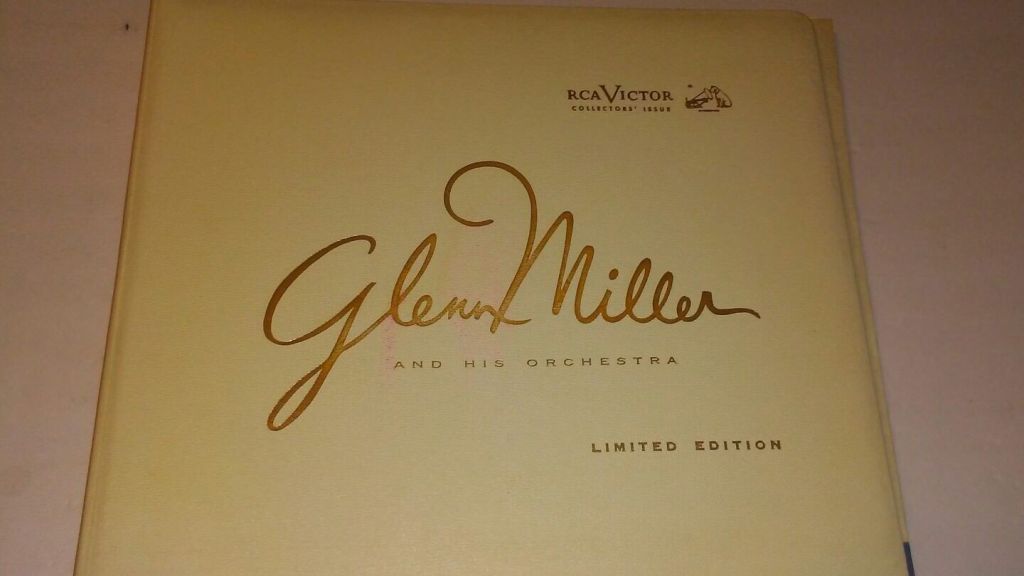

He loved Glen Miller, and gave our mother a gold embossed, white leather album of Miller’s greatest hits. Music filled our house in the evening. Don also loved cars. I once got to go with him to Cicero Avenue in Chicago to buy a Packard, his favorite automobile after the Olds.

I was the one Don took fishing. He taught me, by example, to sit in a boat or on the Lake Michigan pier, not talk, and fish all day. He once took me muskie fishing. We didn’t catch a thing, but a muskie followed the lure to our boat. These experiences were magic.

But over the course of my teen years, Don changed. He stopped making things, fixing his car, and fishing. Instead, he went to night school and worked his way from a tool and die maker to an engineer. He and my mother bought a bigger house; my mother took a fulltime job to finance their American dream. The new life was stressful, and instead of tinkering with something to offset that stress, he relied on a cocktail (and maybe two or three) at night. He developed an edge, and we three sisters avoided him. More than once, I heard our mother say,” I wish we could go back to where we started. He was happiest lying under a car fixing it. We don’t need all this.”

I can’t reliably pinpoint why, but Don lost his essential self, the things that made him Don, his unique creativity. My mother died, and Don lived to be 86. He spent his last few years at the VA hospital, where gradually I watched the curious side of Don return. For him, it was too late for fishing and tinkering, but for me, it was not too late to see the cost of pursuits that deny one’s essential self.

To me, Don is everyman, especially of his generation and veterans of WWII. He’s also a cautionary tale about losing yourself and straying from the things you love. I had the lesson of seeing the changes in Don, from creative young man, to striving type A, and back to a resigned acceptance of what is. Seeing these changes taught me to seek what is authentic in myself. I remember the first time I went to a counselor in my 60’s, and she asked me what my goal was. I told her I wanted to live an authentic life (I wasn’t sure I was, and I wanted to change before it was too late.).

In retirement, I’ve aspired to live authentically. Two books that have supported me are The Creative Age: Awakening Human Potential in the Second Half of Life by Gene D. Cohen, and The Not So Big Life: Making Room for What Really Mattersby Susan Susanka. They both argue that it’s never too late to find what you love and do it. Cohen says that creativity is built into us, not reserved for the young. Karen’s recent blog about the talents and contributions of older women highlights the ways we “elders” can manifest our creativity.

Susanka is more aligned with my personal focus, finding your essential self. I had the cautionary tale of Don in mind in early retirement, when I identified that as a child and a young married adult, I had loved to make things. At the time I was exploring my Norwegian roots, so I thought, why not rosemaling? A door opened to a latent artistic flare and to new friends.

The poet Maggie Smith has a writer’s perspective on creativity and authenticity. She advises staying “elastic” and open to surprise. When I sold our house and moved, I set Smith’s book, You Could Make This Place Beautiful front and center in my new apartment. I didn’t want to dwell on what I’d lost but rather on making my place beautiful and affirming what makes me me.

I believe Smith’s advice can be extended to our lives in retirement or at any time of life. We can make our lives beautiful in our own way. Accessing our essential selves, the things we love to do, our lifelong interests and talents outside of work, can be the foundation for surprising ourselves in retirement. What makes you you? I invite you to explore and enjoy.