Hope is the thing with feathers. I’ve heard that line many times, read the poem over and over, but I’ve never been sure what it means. LitCharts says the poem means, that hope is a strong-willed bird that lives within the human soul—and sings its song no matter what. Almost an a priori trait that we humans hold. But sometimes I worry that “hope” is cheap talk, especially when the speaker of the house, Mike Johnson, says, after the Nashville school shooting: We are hopeful and prayerful.

Maybe another reason I’m unsure about hope is that the last year of my husband Jim’s life, I felt like that thing with feathers had flown away, to other souls perhaps. He declined daily, although at the time, he believed—and tried to persuade me—that if he just exercised more, sat in his compression boots longer, or ate more liver and beets, all would improve. But it didn’t. He’d make plans to go places like the Lakes Area Music Festival in Brainerd or Blue Fin Bay, our special place on Lake Superior. Then, at the last minute he’d tell me to cancel the reservations, never admitting he wasn’t up to it, instead hanging on to hope with an excuse like—”We don’t need to drive all that way when we have a lake right here, and we can watch the music festival online.”

Although I said nothing to Jim, I felt like illness had usurped our lives. I don’t know whether he felt the same way or not, but nightly we’d try to perk up each other by simply sitting together holding hands. In retrospect, hope may have flown away, but love held steady.

It is not my singular experience that hope can be threatened as we age. As Sarah Forbes writes in the Journal of Gerontological Nursing:

The elderly face numerous cumulating losses, such as the loss of a secure future, financial security, functional independence, bodily mobility, significant relationships, societal and familial roles, and bowel and bladder control.

Whew, that makes me not only unsure but discouraged, too. I (The word elderly alone is enough to send me to the mirror to see if I am indeed, elderly).

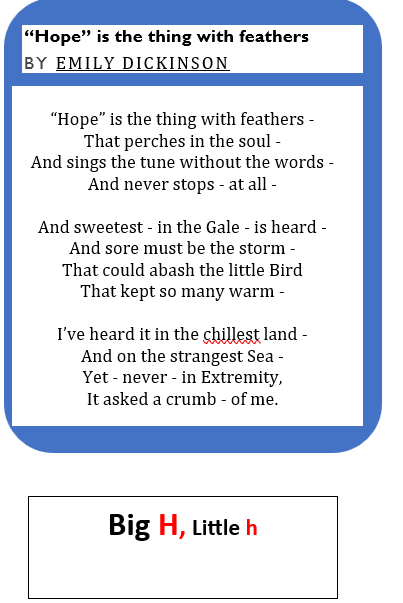

While this quote refers to a unique age group, hope is something we have throughout our lives, from the moment we awaken, “I hope I have a good day,” to falling asleep at night, “Gosh I hope I sleep well.” We hope for good weather or to spend time with loved ones. When I was young, I used to hope that after I paid the bills for the month, there’d be some money left over. Human hopes are a long, long list. In the spirit of my earlier blog about Big P, little p, or Big Purpose, little purpose, I’m labeling these hopes of daily life, little h.

But what about Big H. . .

This morning I picked up the StarTribune and read Pot use rises along with calls for help, and Woman opens fire in Texas church. Tucked further in was an article about climate change and record warmth in Minnesota’s north. Rarely does reading the paper give me hope about anything. Maybe that sells papers, but it sure can add additional weight to those “cumulating losses” that come with age. I call this kind of hope, or lack thereof, Big H, worldly stuff: climate, society, and what kind of future the world’s children will have.

After Jim died, I struggled to regain hope. A family member became seriously ill, I learned of contemporaries dying, and the news remained dark. It felt bleak, and I missed my man who always told me, “Humans will figure it out. I’m hopeful.”

But then, suddenly, when I least expected it, that thing with feathers found me. I’d agreed to teach half time this year for the University. Friends wondered why I said yes to this when I was retired and busy with both Jim and other projects. But something told me I should. The first week of class, I asked students to post short PowerPoints about themselves online so we could get to know one another virtually, to counter an environment where we feel like just a name. And there, in those PowerPoints, perched that bird! I broke into a smile as I read about young people intent on making their lives and the world better. Here are some of the activities these students do in addition to raising families and going to school:

- Volunteer with local animal rescue;

- Advocate for parents and babies

- Change the lives and livelihoods of my people (Gambia);

- Music therapist;

- Mandela Fellow;

- Peer health educator working with drug users;

- Physician working with Disaster Preparedness and Response;

- College success coach;

- Started a non-profit Mother to You (sends medical supplies to Senegal);

- US House of Representatives Senior Policy Advisor; and

- MN Justice Research Ctr, transform current legal system.

There are 45 students in my class so I could go on, but my point is that when I read their PowerPoints, I read hope, an abundance of both Big H and little h. Suddenly this elderly person knew that hope was flourishing all around her.

Although I struggled to feel hope in that last year of Jim’s life, I remember all the little h’s that Jim and I had in the ten years of our marriage. At the same time, he fervently believed that humans would come together and solve the world’s problems. Jim epitomized both Big H and little h. I remember him in the hospital, a week before he died, asking me for his wallet so he could reserve a weekend at Blue Fin when he got better. Maybe Emily Dickenson had it right. If we pay attention, that thing with feathers is all around us.