My husband was in one of his “move everything around” moods, so I had to clear some shelving in the master bedroom. He was moving it into his man-cave. I can’t believe at 79 I’m married to a man-cave sort of man. I thought that was a younger generation affliction.

I also couldn’t believe all the things I’d stashed away in that shelving unit. Besides two shelves of cookbooks, there were assorted threads with needles, several sanding sponges, knitting needles and yarn, workout descriptions ripped from magazines (which I’ve never done), two cameras, charging cords for whatever—I won’t bore you with the rest of the list. Take my word for it, I’ve used that shelving as an “out of sight, out of mind” receptacle.

Having no where to go with the junk, I moved it into my office, thinking I could transfer it to the shelving there—which, when I apprised it, was already full. This wasn’t going to be an easy relocation chore. And I haven’t read—nor do I want to—Marie Kondo’s The Life-changing Magic of Tidying Up. Unlike Karen Rose, who has downsized and confronted clutter twice in the last decade, my moves did not require ditching anything more significant than a dining room table that was too large for our current house.

Just as I was looking for another place to stash my junk—rather than dealing with it—what showed up on Facebook but an article by Ann Patchett called “How to Practice,” which is about clearing out her stuff in response to contemplating death. Was the universe trying to tell me something? I sat down to write this blog—anything to avoid dealing with the mess on my office floor.

*****

After taking a break, I came back to the mess. What could I possibly get rid of to make room for the things I want to keep? And what are the things I actually want to keep, surely not all those sanding sponges? Then I remembered my Aunt Selma (she was a reluctant step-grandmother who preferred to be an aunt). Selma and her husband, Uncle Earl, had a tiny duplex in my hometown of Racine. They lived on the main floor in a fortress of mahogany furniture trimmed in brass. Two pictures I loved adorned the living room walls, peacocks made from feathers in different poses. Their son, Don, my stepfather brought them from Japan after WWII.

As I grew up and as an adult, I watched Earl and Selma age. First they moved to a smaller apartment—gone was the mahogany dining room set. Earl died from Parkinson’s, and Selma moved to another small apartment. She gave my husband and me the mahogany bedroom set. She eventually landed in a Lutheran Home (for the elderly) with only those two pictures, a bed, and a couch. When she died at 99, she had a bed in a nursing home with one of the peacock pictures hanging over the head of the bed. Selma’s life kept shrinking. She knew it, she’d rationalize it, telling me that she no longer liked caring for a house.

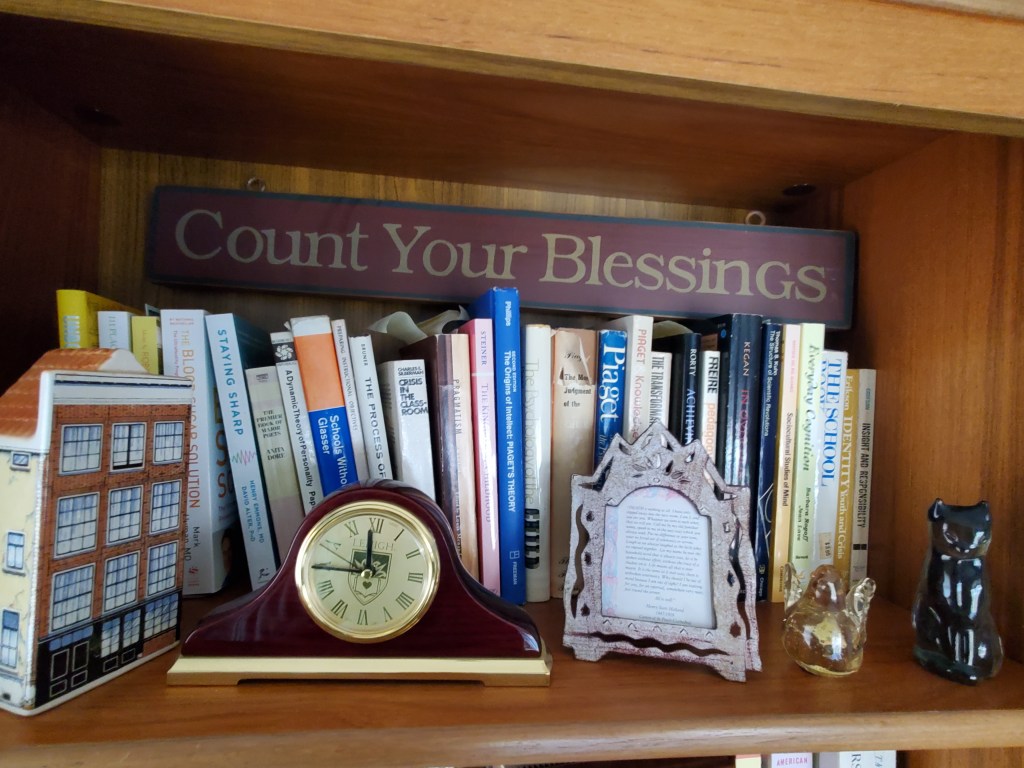

So here I was, wondering what to get rid of and whether my life was also shrinking. When do we shift to reverse and instead of accumulating, start donating? When is it time to start shrinking our lives? I pondered the stuff on my office floor; I noted how crowded my office is, and the books I no longer read (mostly about Piaget or other child development theories – along with and the various – previous and sometimes forgotten — crises in education).

Then I perused the stuff on my shelves. Among them, a replica of the Anne Frank house, which I bought on my first trip to Europe; the clock my colleagues at Lehigh University gave me when I moved back to the Twin Cities; a crystal bird I won for scoring a birdie in the golf league I belonged to as a stay-at-home-mom; a framed card about death that I found in the last book my husband Gary read before he died (It was about J. Edgar Hoover. I kept telling him to read something more uplifting.); and a cut crystal cat that belonged to my mother, my children and I picked it out together for her. These items weren’t just stuff! They were symbols, memories of life stages, places, and relationships—these were the stuff of love

How could I possibly let any of these items go? Karen’s life in stuff! I thought about our last blog—which apparently didn’t inspire our readers all that much—about legacy. These were part of my story, my legacy, and I wasn’t ready to let go. Well, maybe I could ditch some of the books and a couple of the sanding sponges.

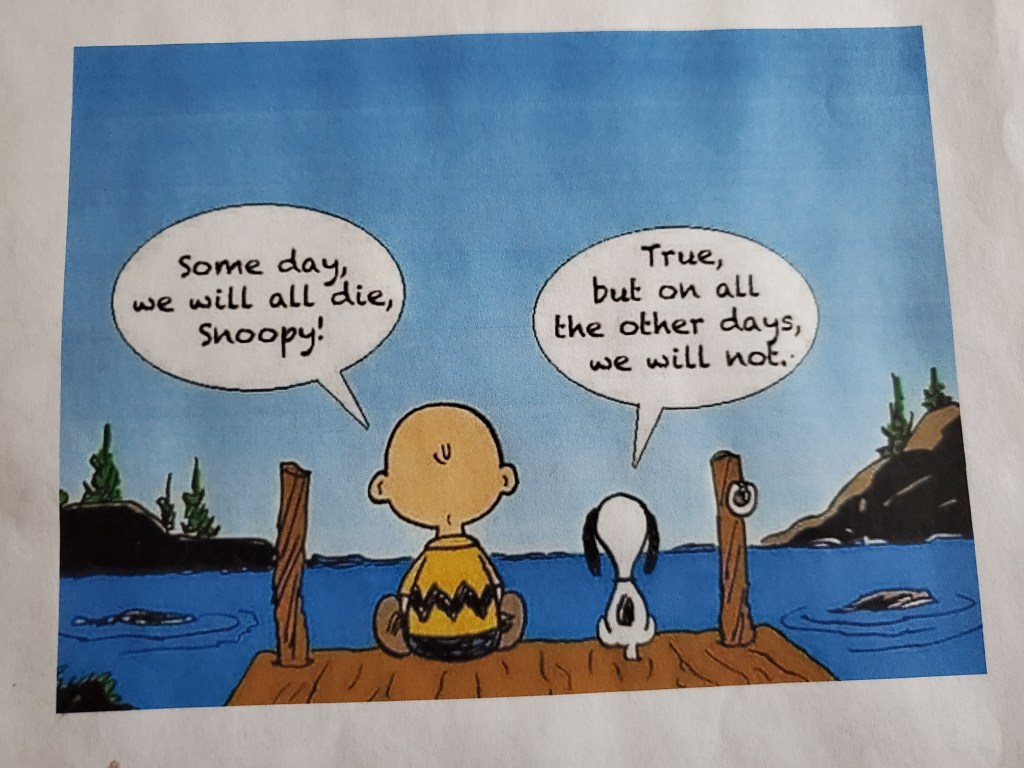

Taking stock of all I’ve accumulated reminded me of the many conversations my husband and I have about moving some place smaller—I’d have to deal with these things. That brought me back to Aunt Selma and the shrinking life. My life would and will shrink. These thoughts led inevitably to death, knowing that I, too, will die, and it’s coming sooner than I expected when I was in my 40’s and 50’s. I used to tell my grandchildren that someone has to be the first person to live forever, why not me? But I’ve stopped saying that.

For a brief minute I pictured my children sitting around cleaning out my office after I die.

“Why do you suppose she saved this?” they would wonder, holding the Lehigh clock that no longer works or the cheap crystal birdie. I don’t know what they’d say about the sanding sponges. Maybe I should put a little label under each item describing its importance—might help me, too, if I go senile.

I thought of something Karen Rose’s husband says, “if it is smaller than a brick and has sentimental value, keep it. Otherwise, seriously consider giving it away.” Whew, I was off the hook. Most of my mementoes are smaller than a brick, although the embodied meanings are more than sentimental. I’m not ready to let go. For the time being, I won’t do anything until I get tired of walking around the mess on my office floor. I’m not dying yet, which leaves me wondering how long will it take until I reckon with death and move one more iota towards acceptance? For now, I’ll continue to treasure my artifacts of memories. I’m just not ready to shift into shrink.